Fundamentals

of Operational

Excellence #2

Enable Agility Through

Organizational Muscle Memory

“The right decision is the wrong decision if it’s made too late.”

-Lee Iacocca

Summary

- The pace of change in every industry requires rapid and constant strategy adjustments, so consistent execution requires agility

- Traditional methods for ensuring consistent execution make the system very lethargic, and need to be re-thought to allow consistency and speed

- Agility can be achieved by building in organizational muscle memory for how the organization evaluates and reacts to changes

Operational Excellence, as we’ve defined it, is “delivering leading performance across all measures of value”. This, of course, requires both a sound strategy and consistent execution of that strategy, and this is where it gets tricky. The pursuit of consistent execution values stability and repetitiveness. When success is found, we want to lock it in through things like standards, procedures and work flows so it can be repeated. The more success is found, the more we desire to lock in that success. This all works great, so long as the conditions that created that success don’t change.

The challenge is that no strategy is immune from change, especially these days where “change is the new normal”. According to a recent study, the average tenure of companies on the S&P 500 was 33 years in 1964. Today, this figure has dropped to 24 years and is expected to shrink to only 12 years by 2027. Keeping up with this rapid rate of disruption and turnover requires a strategy that can quickly adapt.

Operational Excellence and Agility

McKinsey & Company illustrates this point well with their Organizational Health Index (OHI). The index data shows that companies with high OHI rankings generate total returns to shareholders three times higher than those with low OHI. Interestingly, they also found a strong correlation between “Agility” (the ability to adapt quickly while still executing reliably) and OHI, with 70% of “Agile” companies also being in the top quartile of OHI.

The obvious conclusion is that long-term success requires stability (the ability to execute consistently) and speed (the ability to respond quickly to new challenges).

In other words, agility is a prerequisite for Operational Excellence in today’s environment.

The implication is less obvious: how are companies supposed to achieve consistency and stability while also reacting quickly to change, when our normal toolbox for achieving consistency relies on “locking-in” success? The more we lock in, the more “things” we need to alter to keep up with changes in strategy and thus the longer it takes to change.

A common misconception is that agility requires a balance between speed and stability. If stability is achieved through control mechanisms like standards, procedures, formal processes and the like, then the trick must be in finding the right balance of having enough controls without overdoing it. This idea is debunked by the data; most companies (58%) in the McKinsey study were right in the middle of the four quadrants, effectively achieving a “balance” between speed and stability, but still falling short of being “Agile”.

Instead of viewing it as a matter of compromise between speed and stability, we need to think of it as a matter of maximizing both. If traditional methods for ensuring stability sacrifice speed, then we need to re-think the methods we rely on for ensuring stability.

Unlocking Agility through Organizational Muscle Memory

Athletes are great examples of agility and studying how an athlete develops his or her craft reveals many secrets to organizational agility. Athletes train for years to develop the necessary physical ability to execute in high-stress situations. Highly trained athletes are so well coordinated that they can make superhuman-like feats almost seem easy. We take for granted the billions of neurons that are firing in their brain, at hundreds of times per second, that make that motion look so effortless. Those commands within their brains are so hard-wired that the athlete hardly realizes in the moment what they are doing – their motions are so engrained that their bodies just react. We often call this muscle memory, and it’s a key component of agility.

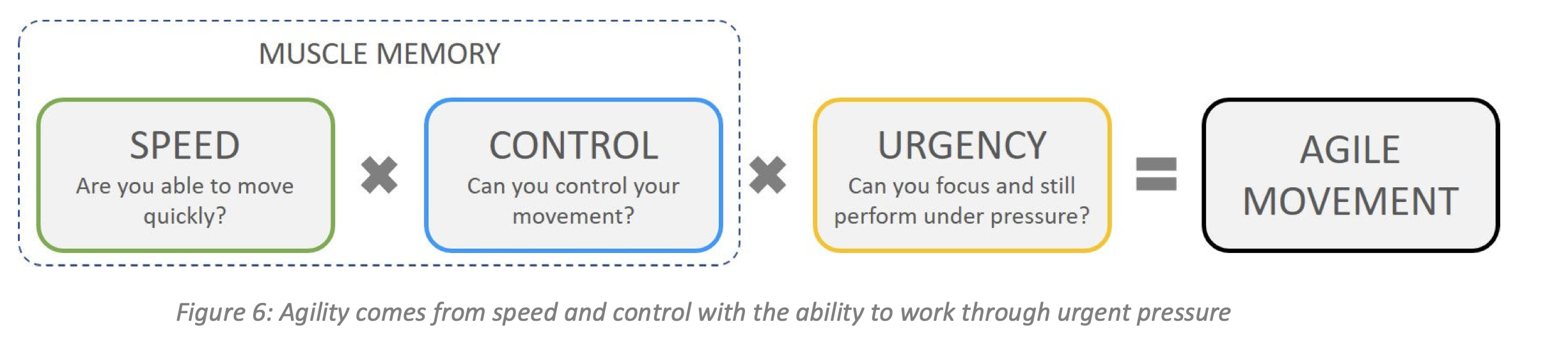

Moving with agility requires three things:

- Speed: This refers to the ability, whether physical or otherwise, to move at the desired pace.

- Control: This refers to the ability to control your movement at the desired speed. Since agility is only useful if it results in rapid movement towards a desired direction, some level of control is necessary. Some people can move very quickly but lose repeatability and accuracy, especially with unrehearsed movements

- Urgency: This refers to the desire or need to move quickly, and it is the true test of agility. Agility must continue to perform as expected even under heightened pressure and urgency of real-world tests to be useful

The Danger of Unstructured Urgency

When many leaders sense their organization is moving too slow, they tend to focus on increasing the sense of urgency. For instance, they may re-iterate the need for rapid improvement due a challenging competitive environment. They might increase urgency through “empowerment” messages that encourage employees to act on their own rather than waiting for someone else to address a known issue. This works in limited instances, but over time, increasing the sense of urgency without enabling speed or earning control often leads to one of two scenarios:

- Organizational Gridlock: Rookie athletes sometimes experience this. They have the physical ability to move quickly, and they know the urgency, but lack of experience leads to indecision and hesitation, and that split-second makes all the difference in the outcome. Organizations do the same thing. Under increased urgency, organizations without control lack confidence in making faster decisions and can end up in a gridlock of indecision. Over-reliance on consensus or data is often a mask for this lack of decision-making confidence.

- Organizational Fatigue: Take an average runner with a high degree of confidence in his or her ability to run without falling and put them in an emergency situation, and that runner might run faster than they’ve ever run before. However, regardless of the sense of urgency or level of control, some people will never be able to run as fast as an Olympic runner, and certainly not for any sustained period of time. Some organizations have a sense of urgency, and in the heat of the moment, they can round up the troops and make rapid changes. However, without sustainable mechanisms for speed, as the fire drills become more common employee fatigue and even resentment can increase.

The only way organizations can operate in an agile and sustainable way is to make it the norm. Like an athlete practices to simulate game-time conditions, organizations shouldn’t wait until the pressure is on to learn to move quickly.

Creating an Agile Organization

When we examine conventional methods that companies use for increasing consistency and stability, we notice they all have something in common. Think about how most companies go about increasing stability – they assess a product or process, find “incidents” where something isn’t quite right, and create controls against them. These controls, if shown to be successful, become embedded throughout the organization in the form of Best Practices, Policies, Procedures, Standards, Work Flows, and Automation. Over time, everyone should be performing that action in the same way, and thus stability is improved.

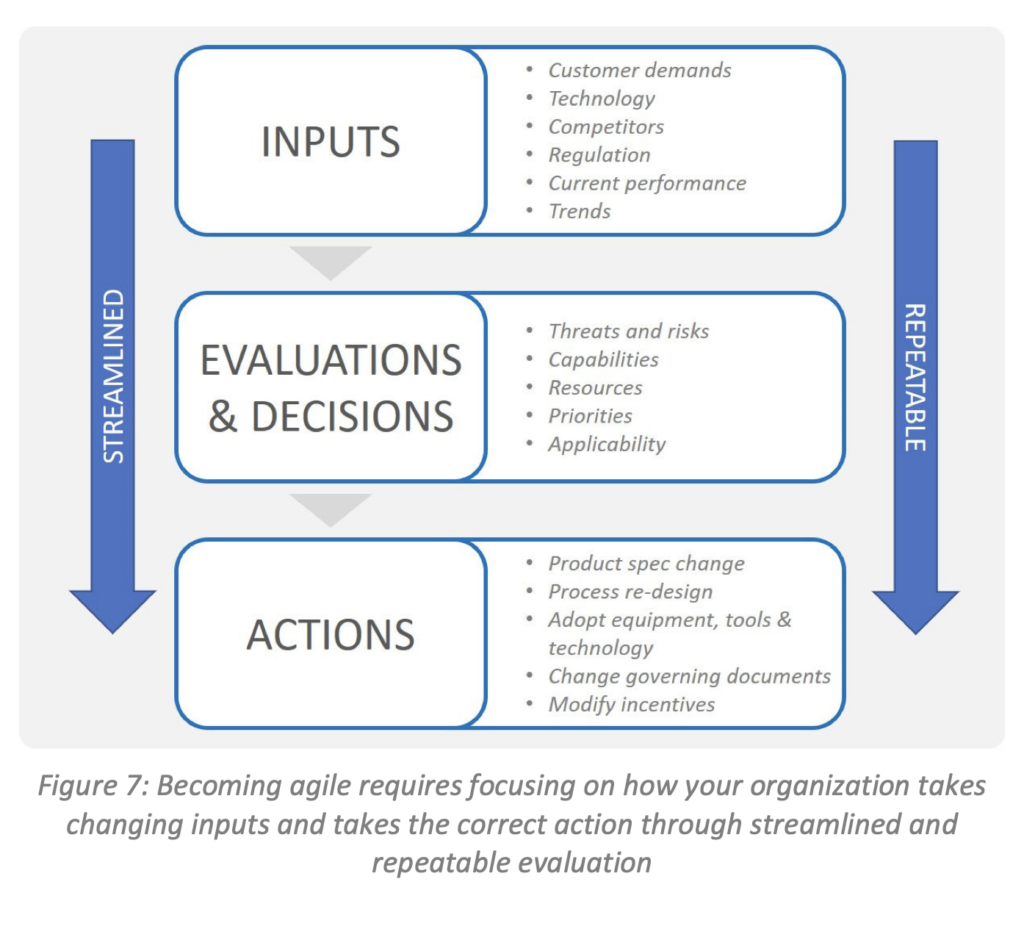

Notice though that these controls are the result of someone taking many inputs and deciding how to perform an action. The focus is on repeating the successful action, but what about the successful decision? In a stable environment, the decisions to change a process or modify a governing document may be rare events, and the actions that lead to success today are likely to lead to success in the future. However, in volatile environments, the lifecycle of a “good” decision is shortened, and the decisions are revisited often. Herein lies the key differentiator for Agile companies – they focus more on the decision algorithms than on the answer.

Agile organizations use repeatable and consistent processes for how management makes decisions (their management system), and they have a well-engrained culture that values using and refining the system. When a decision is needed, they don’t waste time figuring out what information is needed, who can approve the decision, who needs to be consulted, etc. They trust and follow the system that has led to good decisions in the past and can focus more energy on the actual problem rather than sorting out the politics.

In the next few articles, we will dissect how to set up an effective and efficient management system that allows for sustained agility and Operational Excellence.

Creating an Integrated Approach

Designing a Solution that Works for You

This post is an excerpt from the white paper “The Fundamentals for Transforming Your Organization Through Operational Excellence.”

Let’s Talk

We will help you overcome strategic challenges to realize the business value you seek.